Where do storks live?

Distribution area of the white stork in Europe: In 16 countries, we have already identified villages or communities that are exemplary in their efforts to protect these charismatic large birds.

© EuroNaturThere is hardly any bird in Europe as well-known as the white stork. Unlike its secretive relative the black stork, the white stork is a culture follower. It actively seeks the proximity of humans, whether breeding on rooftops or electricity pylons or foraging on freshly mown meadows, behind tractors. Despite its popularity, the white stork is nowhere near as common as it used to be. Large populations are found mainly in Spain and Poland, as well as in the Baltic region.

To live, storks need open landscapes such as flood plains, extensively farmed meadows and pastures or cultivated landscapes with nutrient-rich small water bodies. However, due to flawed agricultural policy, such habitats are becoming increasingly rare.

-

A network for storks

Stork characteristics

The neck and legs are stretched out long in flight: This is clearly a stork.

© Bruno DittrichThe white stork is one of Europe’s biggest birds. When standing, it measures about 95 to 110 centimetres and it has a wingspan of around 183 to 217 centimetres. The white stork is easily recognisable by its white plumage, its black wing and shoulder feathers as well as its long red bill (measuring 14-19 centimetres) and its red legs. When foraging for food, the white stork strides sedately across meadows and pastures, its neck straight, leaning slightly forward. In flight its wingbeats are slow and regular. Unlike herons, storks fly with both their neck and legs outstretched. As “gliders”, they use thermals to soar, their wings held still, high into the sky. We know from monitoring ringed storks that they can live to be up to 39 years old.

What do storks eat?

Plastic is also becoming more and more of a problem for storks. The adult birds mistake the waste for prey and carry it into their nests to feed. Feeding the young birds with plastic has fatal consequences.

© Lorenz HeerWhite storks are definitely not fussy eaters. Their preferred foods are small mammals, frogs and large insects such as grasshoppers. But they also eat reptiles, fish and occasionally the eggs and chicks of ground-nesting birds. In the first weeks after birth, stork parents mainly feed their young earthworms and insect larvae.

Plastic in the environment is dangerous in this context. White storks cannot distinguish between earthworms and “rubber worms”. The adult birds carry the supposed food to the eyrie and regurgitate the food mash for the young. The fatal outcome: the young starve to death with a full stomach. The plastic is also dangerous because it can lead to intestinal blockages and internal injuries.

Storks have developed a variety of hunting techniques for finding food. They grab insects and worms whilst striding out with their head and beak pointing downwards. When hunting for mice, the majestic wading birds stand completely still before then striking at lightning speed.

Reproduction and social behaviour of storks

White storks mating

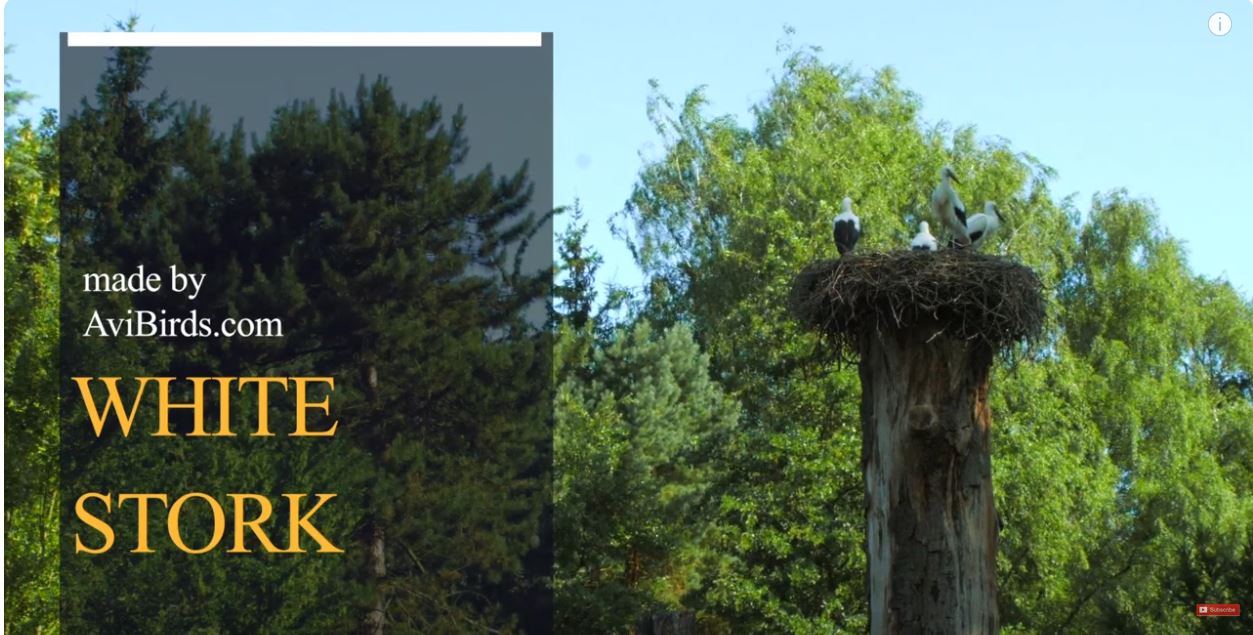

© Bruno DittrichDepending on their breeding ground, Central European white storks return to the previous year’s nesting site from the end of February through to the beginning of April. The males usually arrive a few days before the females in order to occupy the best territories. To greet its mate arriving at the nest, a stork will make a loud rhythmic clattering noise with its bill. This is why, in German folklore, the stork is also known as “Klapperstorch” (clatter stork). The nest is built or repaired by the male and female together and can reach enormous proportions; nests of up to two metres in diameter and three metres high have been seen!

After mating, the females usually lay three to five eggs and both the male and female take it in turns to brood them. During the first month of life, the young are constantly guarded by an adult bird. After about two months, the nestlings fledge but are still provided with food by the parents for another two to three weeks. At around two and a half months, the young storks are independent. They reach sexual maturity at around three to five years of age and it is only then that the young birds return to the nesting site. In the intervening period, they live in the overwintering areas.

Are storks threatened?

Storks walking behind tractors are a familiar sight. However, the conversion of wet grassland into intensively used fields is a negative development for white storks.

© Alper Tüydeş

Strangled white stork on an unsecured power line: This can be remedied by securing existing power lines and laying future power lines underground.

© Matthias PutzeThe primary threat to the white stork is habitat loss. The drainage of wet meadows robs storks of their basic food supply. In the countries of Central Eastern Europe, intensification of agriculture, particularly as a result of EU accession, is a major threat to storks.

Following dramatic population declines in the second half of the 20th century, numbers have recovered in some regions of Europe, for example, in Germany and France. It is likely that the main reason for this is improved food supply in Spain where, in recent years, more and more storks have been overwintering. Recently, white storks have even bred successfully in Great Britain again, after an absence of hundreds of years.

In addition to habitat loss and the consequences of the climate crisis, it is primarily power lines that pose a deadly danger to storks (and other large birds) through electrocution or collision. As long-distance migrants, storks are also exposed to many dangers on their migration routes. In particular, individuals from the Eastern European population - which fly to Africa via the Bosphorus and the Middle East - fall victim to poachers in large numbers.

Under the European Birds Directive, the white stork is listed in Annex I, which details species that are particularly endangered and worthy of protection. In the long term, the conservation of the white stork and its habitats can only be achieved through a change in agricultural policy, such as through the restoration of wet meadows.