How satellites help to protect Europe’s ancient forests

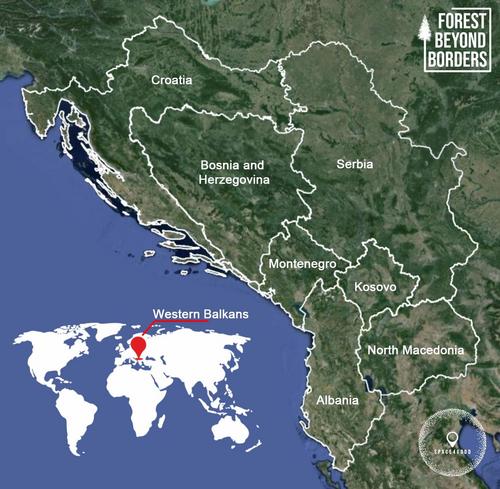

In these seven countries of the Western Balkans (*Kosovo in accordance with UN Security Council Resolution 1244 and the advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice), Space4Good and EuroNatur have joined forces with many local partners in the search for ancient and wild forests.

© Space4GoodThere is something eerie about seeing these dots of light gliding through the night sky. Today, satellites orbit the earth as a matter of course and enable navigation systems to determine locations to the nearest metre, provide data for weather forecasts or transmit television programmes. But satellites and nature conservation? Together with our nature conservation partners from seven countries in the Western Balkans, we have indeed ventured into this terrain. We were accompanied by experts from the Dutch start-up company Space4Good. The journey into the unknown had one main goal: to locate the last remaining wild forests in the Western Balkans in order to better protect them and by joining forces with as many allies as possible.

-

About Space4Good

-

What are primeval and natural forests?

"We have broken completely new ground"

Untouched, untamed and inaccessible: the forests in the Boia Mica Valley in the south of the Făgăraș Mountains (Romania).

© Matthias SchickhoferHow can a primeval or natural forest be recognised from space?

Federico Franciamore: Primeval and natural forests leave characteristic fingerprints on satellite images. Every forest has certain patterns and spectral characteristics. For near-natural forests, for example, chaotic structures are typical and, according to how the tree canopy reflects sunlight, we can deduce which tree species occur in the forest. By analysing historical satellite data, we can determine which areas have remained untouched by humans over a long period of time.

Why do we need satellite remote sensing here? Haven't the forests of the Western Balkans already been mapped?

Franciamore: There is still no complete mapping and there are no up-to-date databases. Our aim was firstly to localise primeval and natural forests and secondly to find out how endangered they are. In some places, for example, we were able to determine where deforestation has occurred or is currently taking place. The third and final step was to check whether these areas are already under protection.

Forest experts check the satellite data by making spot checks on the ground. Sometimes drones are also used

© Susanne SchmittYou foresaw the potential of combining remote sensing technology and artificial intelligence with the practical experience of forest conservationists on the ground. How was that achieved?

Franciamore: First of all, we had to define features that could be used to recognise primeval forests on satellite images. We were helped by test areas that we knew for sure were covered in old-growth forests. Then artificial intelligence came into play: We trained a machine learning model to recognise these typical patterns. The result was an initial map that shows where ancient forests are likely to be found and with what probability. The EuroNatur partners in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Albania, North Macedonia, Serbia, Montenegro, Croatia and Kosovo helped to further improve the model with on-site verification checks.

Annette Spangenberg: In some cases, it was more difficult than expected to obtain the necessary data from our local partners. One of the reasons is that this new method also requires a new way of thinking and a new way of working. At the beginning of our collaboration with Space4Good, it was all about finding a common language that would allow us to combine the possibilities of remote sensing technology with the experience of forest conservationists. We have broken completely new ground here.

Franciamore: This continuous exchange was very important and special. EuroNatur has shown a great deal of openness to absorbing even complex technical content and quickly became a competent partner for us. EuroNatur functions as a bridge between the technical side and the people who are active on the ground every day to protect nature. Together, we organised several online workshops in which we taught the basics of satellite remote sensing and brought the network together.

How satisfied are you with the result?

Spangenberg: Creating a dialogue between man and machine was a crucial aspect, but also not easy. We were perhaps a little too ambitious in the beginning. Nevertheless, the initial results show just how much can be achieved with this new approach.

Susanne Schmitt: Thanks to the model, we now have a clear idea, based on evidence, of where primeval and natural forests still exist in the seven Western Balkan countries analysed. This is a valuable basis for protecting them better in the future.

Franciamore: The on-site verification checks prove that our model is very precise. Wherever the map indicated a probability of more than 80 per cent chance of primeval or natural forests occurring, there were indeed some to be found. That is an outstanding result. On the other hand, it unfortunately turned out that many of these forests are not yet protected.

Schmitt: Areas in north-east Albania, for example, are particularly interesting. On the one hand, the model shows that there is a high probability that there are still primeval or natural forests there. On the other hand, it reports extremely large forest losses for these areas in recent years. That is an explosive mixture! Now we need to take a closer look at the situation on the ground and plan the next steps accordingly.

The Space4Good team working with EuroNatur on the "Forest Beyond Borders" (FBB) project. Back row: Rishi Sukul, Biman Biswas, Max Malynowsky

Front row: Hope Byrd, Mariana Silvestre, Liliana Gonzalez, Federico Franciamore.

© Susanne SchmittWhat are the next steps? How can the forest maps help to better protect the forests?

Franciamore: With the help of the technologies, we have created an objective data set. This is particularly important in areas where corruption is a major issue and the natural environment is being exploited in favour of economic interests.

Schmitt: In some locations, the aim will be to achieve the designation of new protected areas. With the help of the map, we can now campaign for this at national and European level. Where protected areas already exist, we need to check whether they offer sufficient protection. Where necessary, we will support our partners in taking legal action against illegal deforestation. Another important goal is and remains the expansion of a strong, cross-border network of forest conservationists, scientists and non-governmental organisations.

Franciamore: Right from the start, we wanted to create a platform where common problems could be discussed. During our online training sessions on satellite remote sensing, it became clear that there are similar difficulties in different countries. Even when illegal deforestation is uncovered, the responsible institutions are doing nothing about it. That is depressing! A strong partner network can provide the necessary support here. Solutions that work in one country may possibly be adopted by others. That's why we gave the project the name "Forest Beyond Borders".

Text and interview: Katharina Grund

A different approach to entrepreneurship

"I am impressed by people who fight for something that is close to their hearts, such as justice or an intact natural environment. For me, Space4Good has become a vehicle for helping such campaigners and the organisations associated with them. We work according to the principle: impact first, business second, which means that we assess every project and every client on several sustainability criteria before we start a collaboration. I gained a useful insight at a meeting of social entrepreneurs at the Impact Hub in Amsterdam, where the focus was on new, sustainable forms of business. I realised that the 'how much' is not nearly as important as the 'why'. Together with organisations such as EuroNatur, Space4Good wants to achieve positive change.

We provide our expertise in the field of space technology and EuroNatur contributes the necessary network - contacts with people who can make a difference on the ground. The "Forest Beyond Borders" project is one of the most complex we currently have, because it is very much about enabling organisations and individuals to use satellite remote sensing for nature conservation themselves. I always see a smile on the faces of my team when it comes to EuroNatur. I would describe our co-operation as a kind of productive harmony. We have the same vision of preserving our nature and regenerating it where necessary."

Alexander Gunkel is the founder and Managing Director of Space4Good